NOTES FROM A NATIVE SON

Is Population the Problem?

Fred Magdoff Posted on monthlyreview.org 2013, Volume 64, Issue 08 (January)

Environmentalists and scientists often refer to the two different ends of the environmental problem as sources andsinks. Thus the environmental limits to economic growth manifest themselves as either: (1) shortages in the “sources” or “taps” of raw materials/natural resources, and thus a problem of depletion, or (2) as a lack of sufficient “sinks,” to absorb wastes from industrial pollution, which “overflow” and cause harm to the environment. The original 1972 Limits to Growth study emphasized the problem of sources in the form of shortages of raw materials, such as fossil fuels, basic minerals, topsoil, freshwater, and forests. Today the focus of environmental concern has shifted more to sinks, as represented by climate change, ocean acidification, and production of toxics. Nevertheless, the problem of the depletion of resources used in production remains critical, as can be seen in discussions of such issues as: declining freshwater resources, peak (crude) oil, loss of soil fertility, and shortages of crucial minerals like zinc, copper, and phosphorus.

In conventional environmental analysis the issue of a shortage or depletion of natural resources has often been seen through a Malthusian lens as principally a problem of overpopulation. Thomas Malthus raised the issue in the late eighteenth century of what he saw as inevitable shortages of food in relation to population growth. This was later transformed by twentieth-century environmental theorists into an argument that current or future shortages of natural resources resulted from a population explosion overshooting the carrying capacity of the earth.

The following analysis will address the environmental problem from the source or tap end, and its relation to population growth. No systematic attempt will be made to address the sink problem. However, the tap and the sink are connected because the greater use of resources to produce goods results in greater flows of pollutants into the “sink” during extraction, processing, transportation, manufacturing, use, and disposal.

In approaching the source or tap problem, we have to recognize there is a finite planetary quantity of each nonrenewable resource that can be recovered economically. In theory, it is possible to calculate when the world will run out of a particular resource, given knowledge of the amount of the resource that exists, technology, costs, and likely demand—though the various factors are often so uncertain as to make firm predictions difficult. However, the amount that can be extracted economically increases when the price of a particular resource increases or new technology is developed—it then becomes economically feasible to exploit deposits that are harder to reach or of less purity and more costly to obtain.

An easier question to answer is whether we are using a given resource in a sustainable manner. For renewable resources, such as water, soil, fish, forests, this means that use cannot exceed the rate of regeneration of the resource. For nonrenewable resources, as with fossil groundwater, fossil fuels, and high-grade minerals, this means that the rate of use can be no greater than the rate at which renewable resources (used sustainably) can be substituted for these nonrenewable resources—that is, the sustainable use of nonrenewable resources is dependent on investment in renewable resources that can replace them. For pollutants the sustainable rate of emission is determined by the degree that they can be absorbed and rendered harmless in the environment.

There are some examples of renewable resources being sustainably substituted for nonrenewable ones, but most have had limited impact. For some resources that are part of modern life—such as many of the metals—there are no foreseeable renewable substitutes. These need to be used at relatively slow rates and recycled as efficiently as possible. And nonrenewable resources are required to manufacture equipment for “renewable” energy such as wind and solar power. By far the largest example of renewable resources being substituted for nonrenewables is the use of agricultural products such as corn, soybeans, sugarcane, and palm oil to produce ethanol and biodiesel to replace gasoline and diesel fuels. But the limited energy gain for most biofuels, the use of nonrenewable resources to produce these “renewable” resources, and the detrimental effects on people and the environment are so great as to make large-scale production and use of biofuels unsustainable.

Resource Depletion and Overuse

There are many examples of justified concern over depletion and unsustainable use of resources—or, at least, the easily reached and relatively cheap to extract ones. A little discussed but very important example is phosphate. It is anticipated that the world’s known phosphate deposits will be exhausted by the end of the century. The largest phosphate deposits are found in North Africa (Morocco), the United States, and China. Although phosphorus is used for other purposes, its use in agricultural fertilizers may be one of the most critical for the future of civilization. In the absence of efficient nutrient cycling (the return to fields of nutrients contained in crop residues and farm animal and human wastes), routine use of phosphorus fertilizers is critical in order to maintain food production. Today much of the fertilizer phosphate that is used is being wasted, leading to excessive runoff of this mineral, inducing algal blooms in lakes and rivers and contributing to ocean dead zones—both sink problems.

We could discuss many other individual nonrenewable resources, but the point would be the same. The depletion of nonrenewable resources that modern societies depend upon—such as oil, zinc, iron ore, bauxite (to make aluminum), and the “rare earths” (used in many electronic gadgets including smart phones as well as smart bombs)—is a problem of great importance. Although there is no immediate problem of scarcity for most of these resources, that is no reason to put off making societal changes that acknowledge the reality of the finite limits of nonrenewable resources. (“Rare earth” metals are not actually that rare. Their price increase in recent years has been caused by a production cutback in China, which accounts for 95 percent of world production, as it tries to better control the extensive ecological damage caused by extracting these minerals. Production of rare earths is starting up once again in the United States and a large facility is planned for Malaysia, where it is being bitterly opposed by environmental activists. The main current issue with rare earth metals is not scarcity at the tap end, but rather pollution associated with mining and extraction—again a sink problem.)

What is important is that the environmental damage and the economic costs mount as corporations and countries dig deeper in mining for resources and use more advanced technology and/or in more fragile locations. Mining companies are using new technologies such as robotic drills and high-strength pipe alloys to drill deeper after the surface deposits are depleted. Seafloor mining is another approach used to deal with declining easy-to-reach deposits. In the beginning of what may well be a major effort to exploit seafloor mineral resources, a Canadian company has signed a twenty-year agreement with the government of Papua New Guinea to mine copper and gold some fifty kilometers off the coast.

Still another way to deal with depleted high-quality deposits is to exploit those of lower quality. In highlighting this development, the CEO of a copper mining company explained: “Today the average grade—the grade is a measure of the amount of copper you can turn into material—is half of what it was 20 years ago. And so to get the same amount of copper from a deposit, you have to mine and process significantly larger quantities of material, and that involves higher cost.” This mining approach creates larger quantities of leftover spoils to pollute air, water, and soil.

The exploitation of the Canadian tar sands is an example of high prices for oil inducing the use of a deposit that is both costly and ecologically damaging. However much damage this extractive operation may do to the environment, it will significantly extend the period that the resource is available, though at higher prices.

There are of course important exceptions to new harder to reach deposits driving or keeping prices higher. For example, with the ecologically damaging hydraulic fracturing combined with horizontal drilling for oil and gas extraction from shale deposits, so much natural gas is being produced in the United States that its price has plummeted. This, however, reflects an extreme undervaluation of the ecological and social costs of fracking, which are immense—and dangerous to both human beings and local and regional ecosystems.

One of the most critical actually occurring resource “tap” problems facing the world is a lack of fresh water. Normally fresh water is considered a renewable resource. However, there are ancient fossil aquifers that contain water that fell literally thousands of years ago. These aquifers, such as those in Saudi Arabia and in North Africa, need to be viewed for what they are—nonrenewable or fossil water. There are also aquifers that are renewable, but which are being exploited far above their renewal rate. The aquifers in the U.S. Great Plains (the Ogallala aquifer), in northwestern India, and northern China are all being exploited so rapidly relative to recharge rates that water levels are falling rapidly. This means deeper wells must be drilled and more energy used to raise the water greater distances to the surface. Drilling deeper wells is clearly only a temporary “solution.” In addition, there is so much water taken, mainly to irrigate crops, that China’s Yellow River, the Colorado River in the United States and Mexico, and the Euphrates and Tigris Rivers in the Middle East rarely reach their normal outlets to the sea. Thus, the situation with water (as with the ocean fisheries) makes it clear that even a renewable resource can be overexploited with detrimental consequences. China is engaged in a costly and ecologically questionable effort to bring water from the headwaters of the Yangtze River in the south to the increasingly parched northern regions.

Another current critical resource problem is agricultural soil, which is related to a number of other issues (see below), including water availability. It takes between 500 and 1,000 pounds of water to grow one pound of grain. Thus, water-short countries are searching for other regions of the world, in land grabs, to grow food for their people. With the neoliberal emphasis on “free trade” as a cure-all, it might seem that all a country with a food shortage needs to do is to purchase food on the “free” international market. But with the severe pain caused by the rapid rise of food prices on international markets in 2007–2008, again in 2011, and to a lesser extent in 2012, a number of countries are trying to protect their people by having food grown abroad, but specifically for them.

Sovereign wealth funds and private capital purchase or lease land under long-term agreements.The spikes in food prices over the last five years have encouraged major importers to bypass international markets to buy needed food and to assure supplies by obtaining land in other countries. Governments (such as China, the United Arab Emirates, South Korea, Egypt, India, and Libya) and private capital have been buying up or leasing under very favorable terms a truly astounding amount of agricultural land in Africa (mainly), southeast Asia, and Latin America—involving some 70 million hectares (about 170 million acres). It is estimated that since 2000, 5 percent of Africa’s agricultural land has been bought or leased under long-term agreements by foreign investors and governments. These agricultural land grabs are partially an issue of water. The land purchases and leases include the implicit right to use water that in some cases may actually exceed the quantity of locally available water.

Saudi Arabia, now a significant participant in the land grabs, decided to use some of their oil to power pumps in order to irrigate large areas of desert land. After 1984, fossil water represented more than half of all water used in the country. At its maximum use in the mid–1990s, more than three quarters of the water used was mined from prehistoric deposits. As a result, for some years the country was actually self sufficient in wheat—growing enough to feed this staple to over 30 million people. But by 2008, the fossil aquifer had been nearly mined out, and the country now must import all of its wheat.

There are other reasons, in addition to its relation to water shortages, for the growth of global land grabs—from the use of land to grow biofuel crops to greater consumption of meat (with greater use of corn and soybeans to feed animals) to weather-related crop failures to commodities speculators driving prices up when shortages occur. Private capital—with British firms leading the charge—has been especially interested in controlling land in Africa to produce biofuels for European markets. All of the land grabs displace people from their traditional landholdings, forcing many to migrate to increasingly marginal land or to cities in order to live. The results are more hunger, rising food prices, expanding urban slums, and frequently increased carbon dioxide emissions.

In his important book The Land Grabbers, Fred Pearce writes:

Over the next few decades I believe land grabbing will matter more, to more of the planet’s people, even than climate change. The new land rush looks increasingly like a final enclosure of the planet’s wild places, a last roundup of the global commons. Is this the inevitable cost of feeding the world and protecting its surviving wildlife? Must the world’s billion or so peasants and pastoralists give up their hinterlands in order to nourish the rest of us? Or is this a new colonialism that should be confronted—the moment when localism and communalism fight back?

The general problem of rapid resource depletion that occurs in the poor countries of the world is frequently a result of foreign exploitation and not because of a country’s growing population. The exploitation of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s natural resources by shady means—“opaque deals to acquire prime mining assets”—organized through shell companies by British and Israeli capital is an example of what can happen. As Duke University ecologist John Terborgh described following a trip to a small African nation:

Everywhere I went, foreign commercial interests were exploiting resources after signing contracts with the autocratic government. Prodigious logs, four and five feet in diameter, were coming out of the virgin forest, oil and natural gas were being exported from the coastal region, offshore fishing rights had been sold to foreign interests, and exploration for oil and minerals was under way in the interior. The exploitation of resources in North America during the five-hundred-year post-discovery era followed a typical sequence—fish, furs, game, timber, farming virgin soils—but because of the hugely expanded scale of today’s economy and the availability of myriad sophisticated technologies, exploitation of all the resources in poor developing countries now goes on at the same time. In a few years, the resources of this African country and others like it will be sucked dry. And what then? The people there are currently enjoying an illusion of prosperity, but it is only an illusion, for they are not preparing themselves for anything else. And neither are we.

Thus, resource problems—both renewable and nonrenewable—are real and are only going to get worse under the current political-economic system. Everywhere both renewable and nonrenewable resources are being used unsustainably by the above criteria. In some countries the high population relative to agricultural land and the lack of dependable quantities of exports to purchase food internationally creates a very precarious situation. However, the general resource depletion and ecological problems—at the global scale, as well as within most countries and regions—are primarily the result of the way capitalism functions and economic decisions are made. Central to this is the continuing exploitation of the resources of the poor countries by corporations and private capital. Maximizing short-term profits trumps all other concerns. What happens as resources are in the process of being ruined or depleted? There is a scramble, frequently violent, for control of remaining resources. But what will happen, what is the “game plan,” after even the hard to reach, expensive, and ecologically damaging deposits are fully depleted? Capital has only one answer to such questions, the same as the one attributed to Louis XV of France: “Après moi, le deluge.” What other conceivable response could it give?

The Accumulation of Capital is the Accumulation of Environmental Degradation

The root of the problem lies in our mode of production. Capitalism is an economic system that is impelled to pursue never-ending growth, which requires the use of ever-greater quantities of resources. When growth slows or ceases, this system is in crisis, expanding the number of people who are unemployed and suffering. Through a massive sales effort that includes a multi-faceted psychological assault on the public using media and other techniques, a consumer culture is produced in which people are convinced that they want or “need” more products and new versions of older ones—stimulating the economy, and thus increasing resource depletion and pollution. It creates a perpetual desire to have new possessions and to envy those with more stuff. This manufactured desire includes the poor, who aspire to the so-called “middle-class” standard of living depicted on television and in the movies.

Because it has no other motivating or propelling force than the accumulation of capital without end, capitalist production has negative social and ecological side effects, usually referred to by economists as “externalities.” In reality these are in no way external to production. Rather they are “social costs” imposed on the population in general and the environment by private capital. In its normal functioning, the system creates fabulous wealth for a certain few—now referred to as “the 1%” (though the 0.1% would be more accurate)—and very great wealth for the richest 10 percent, whose consumption of stuff is responsible for much of the ecological damage and resource use in the world. At the same the same time capitalism generates a significant portion of the population whose basic needs are not being met.

Let’s Talk Population

There are a number of people and organizations that feel that we must drastically reduce the human population because we will soon run out of nonrenewable resources. Behind the difficulty in tapping resources lies the fact that too many people are accessing them. Some maintain that resources are already scarce per capita in the world at large, and, thus, the resource crises and resources wars are actually here, right now. There is no need to look very far to find evidence of frictions, conflicts, and even some wars over access to resources—especially oil and gas, water, and agricultural land. The U.S. wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the U.S. military bases and support provided to local governments in the Middle East and Central Asia have been lately about access to, or control, of oil. These actions and relations are not simply about overpopulation, however, but are rather a continuation of a capitalist colonial and imperial history of exerting influence in these resource rich regions. Basic to the structure of globalized capitalism is that a small minority of the world population in the rich countries dominates large parts of the world, robbing them of their resources.

The productive aquifers on the Palestinian West Bank, for example, must be factored into understanding Israel’s reluctance to end the occupation and return to its pre–1967 war borders. In weaker countries where no ruling class is in firm control, internal conflict and even civil wars may arise as a result of efforts to profit from the exploitation of resources.

A whole host of countries, including China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia are in conflict over ownership of yet to be discovered, but promising, oil deposits under the sea floor along with other potential resources in the South China Sea. There are also disputed sea floor boundaries in the eastern Mediterranean, where Israel has discovered a large deposit of natural gas. Additionally, there is the potential for conflict over the Caspian basin petroleum deposits.

Recently, the melting of sea ice in the Arctic is opening up the Arctic waters to oil exploration, creating an “Ice Cold War,” as it has been called, involving the United States, Canada, Russia, Denmark, and Norway. Michael Klare, in his book The Race for What’s Left, argues that “the world is entering an era of pervasive, unprecedented resource scarcity.”

Usually such conflicts are treated as mere byproducts of growing population and international competition, but a closer analysis demonstrates that capitalism and the incessant drive for expansion that it inculcates, along with its imperialist tendencies, are mainly at fault. Attempts to reduce the environmental problems to the “population bomb” are therefore frequently crude and distorted. A variety of side issues and “straw persons” are put forward, diverting attention from the heart of the matter. As a result, it is important to clarify a number of such issues and get potential stumbling blocks, related to population specifically, out of the way before continuing with this part of the discussion. Our starting points should be:

- All people everywhere should have easy access to medical care, including contraceptive and other reproductive assistance.

- As living standards rise to a level that supplies family security, the number of children per family tends to decline. But, depending on the circumstances, there may be good reasons for poor women and men to have fewer children even before they have more secure futures and for individual countries to encourage smaller families.

- There are poor countries where overgrazing, excess logging of forests, and soil degradation on marginal agricultural land are caused by relatively large populations and the lack of alternate ways for people to make a living except from the land. This problem may be worsened by the low yields commonly obtained from infertile tropical soils. But we also need to recognize that these problems are not only an issue of population density. Displacement of farmers by large-scale farms causes some to seek new areas to farm and graze animals—using ever more marginal or ecologically fragile land.

- Some countries have populations so large relative to their agricultural land that importing of food will be needed into the foreseeable future. One of the largest of these nations is Egypt, with a population of over 80 million people and arable land of 0.04 hectares (less than one tenth of an acre) per capita. These countries are condemned to suffer the consequences of rapid international market price hikes that occur frequently and of having to maintain significant exports just to be able to get sufficient hard currency to import food. There are other countries—such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Qatar—that have a larger population than what can be sustained by available water/food resources, but each of them can currently use oil and/or other commercial income to obtain sufficient food for their populations. Similarly, a rich developed country like the Netherlands is able to draw unsustainably on resource taps and dispose of its environmental effluents in waste sinks at the expense of much of the rest of the world.

- All else being equal—which, of course, it never is—larger populations on the earth create morepotential environmental problems. So population is always an environmental factor—though usually not the main one, given that economic growth generally outweighs population growth and environmental degradation arises mainly from the rich rather than the poor.

- If we assume that all people will live at a particular standard of living, there is a finite carrying capacity of the earth, above which population growth will not be sustainable because of rapid depletion of too many resources and too much pollution. For example, it is impossible for all those currently alive to live at what is called a “Western middle-class standard”—for to do so we would need more than four Earths to supply the resources and assimilate pollutants.

- There are currently approximately 7 billion people in the world and, given current trends, the population is expected to be around 9 billion in 2050, and over 10 billion by 2100.

One of the main approaches taken by people whose primary concerns are resource use and “overpopulation” is to push birth control efforts in poor countries, mainly through programs aimed at contraceptive use by women. Since these are countries in which populations are growing at fast rates (with growth in sub-Saharan Africa the most rapid), it seems at first blush to make some sense to concentrate efforts on this issue. But when looked at more deeply, it is clear that this is not a solution to the real problems—global-scale nonrenewable resource depletion and environmental degradation—that so concern these people.

David Harvey has explained the problem of concentrating on population issues as follows: “The trouble with focusing exclusively on the control of population numbers is that it has certain political implications. Ideas about environment, population, and resources are not neutral. They are political in origin and have political effects.” One of the peculiar things about those so very concerned with overpopulation and the environment is that they do not seem especially interested in investigating the details of what is actually happening. There is little to no discussion of how the economy functions or of issues involving economic inequality. Also there is apparently no interest in even thinking about an alternative way for people to interact with each other and the environment or how they might organize their economy differently. (There are important and interesting examples of local efforts at different ways of relating/organizing such as cooperative stores, worker-owned businesses, Community Supported Agriculture farms, transition communities, and co-housing. Although these examples are very important—because they are concrete demonstrations of alternative ways of people interacting with each other and the environment—they do not add up to a new economy or new society that operates with a completely different motivation, purpose, and outcome than capitalist society.)

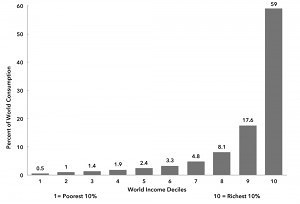

It is only common sense that the more wealth a person or family has, the more stuff they consume and, therefore, the more resources they use and the more pollution they cause. But the almost unbelievable inequality of wealth and income at the global level has striking effects on the consumption patterns (see Chart 1).

What is immediately apparent from Chart 1 is that the 10 percent of the world’s population with the highest income, some 700 million people, are responsible for the overwhelmingly majority of the problem. It should be kept in mind that this is not just an issue of the rich countries. Very wealthy people live in almost all countries of the world—the wealthiest person in the world is Mexican, and there are more Asians than North Americans with net worth over $100 million. When looked at from a global perspective, the poor become essentially irrelevant to the problem of resource use and pollution. The poorest 40 percent of people on Earth are estimated to consume less than 5 percent of natural resources. The poorest 20 percent, about 1.4 billion people, use less than 2 percent of natural resources. If somehow the poorest billion people disappeared tomorrow, it would have a barely noticeable effect on global natural resource use and pollution. (It is the poor countries, with high population growth, that have low per capita greenhouse gas emissions.) However, resource use and pollution could be cut in half if the richest 700 million lived at an average global standard of living.

Thus, we are forced to conclude that when considering global resource use and environmental degradation there really is a “population problem.” But it is not too many people—and certainly not too many poor people—but rather too many rich people living too “high on the hog” and consuming too much. Thus birth control programs in poor countries or other means to lower the population in these regions will do nothing to help deal with the great problems of global resource use and environmental destruction.

Population Declines and Capitalist Economies

As Marx wrote, “in different modes of social production…there are different laws of population growth.” Capitalism has its own laws in this respect. Because growing populations help stimulate economies and provide more profit opportunities, capitalist economies have significant problems when their populations do not grow, do not grow fast enough, or actually decline. A growing population produces the need to build more housing, sell more furniture and household goods, cars, etc. Germany is an interesting example—its population has been shrinking since 2005 and its labor force has been decreasing slowly, reaching about 43 million people in 2012. Over the next half century, it is predicated that Germany’s total population will decrease by some 20 percent—by 17 million people out of a population of 83 million. You might ask, if zero population growth is so difficult for a capitalist economy, then why is Germany weathering the current economic crisis better than its European brethren?

Part of the answer lies in the fact that during the early 2000s, Germany sought to increase profitability of its businesses by enhancing capital’s power over labor. Former Chancellor Gerhard Schroeder boasted “we have restructured the labor market to enhance its flexibility….With our radical reforms of the country’s social security systems, most notably health care, we have paved the way for the reduction of nonwage labor costs.” This change has given Germany an edge, especially with respect to other EU economies, and has helped lead to a resurgence of exports—much of these going to other EU countries. Another reason for Germany doing relatively well is that the country is the second largest exporter in the world, with some $1.5 trillion in exports in 2011—well over 50 percent of its GDP (exports from the United States amounts to about 15 percent of its GDP). It has had a positive current account balance for a decade, over the last eight years it has been greater than 4 percent of its GDP. Thus, through exports, an economy can grow even in the absence of the economic demand that would come from growing number of households. But this outlet of being a net exporter is not available to all countries (practical problems make this so and it is also, of course, mathematically impossible for all countries to be net exporters).

And then what happens when labor shortages occur in Germany? Labor can be imported. Germany in fact has relied heavily on imported labor, with some 4.5 million foreign relatively low-skilled “guest workers” between 1960 and 1973. Germany is now importing fully trained labor, mainly from the European Union. Without having to bear the costs of education and training, Germany is getting quite a bargain. A recent Los Angeles Times headline stated: “As EU migrants flood Germany, some nations fear a brain drain.”

So this is how capitalism deals with zero or negative population growth within a country—the country exports as much as possible and imports the labor it needs when it runs into labor shortages as its population ages and as economic upswings require more workers. With regard to the issue of Germany being a net exporter—clearly if some countries export more than they import there must be other countries that import more than they export. Thus if population was to decline in all countries at the same time, neither of the avenues that Germany is pursuing—increasing net exports and importing labor as needed—can possibly be open to all countries simultaneously.

Although the German economy partly as a result of such means has done better than others in the European Union, there are many reasons to think that trouble lies ahead, and not only because of the recession that has engulfed Europe. One of the ways that capital deals with the slow potential for growth in the “home country” is to invest abroad (export capital). “Since the millennium, net investment in Germany as a share of GDP has been lower than at any time in recorded history, outside the disastrous years of the Great Depression. The German corporate sector has invested its more than ample profits, but it has done so outside the country. The effect of this flight of private money has been compounded by Berlin’s campaign to enforce balanced budgets, which has prevented meaningful investment on the part of the public sector.” This does not point to the continuation of the German “jobs miracle.”

Japan is another country with a shrinking population. For historical and cultural reasons it is not as open to importing labor (although it does import some) as Germany. However, the stagnating economy has been kept afloat through exports and huge amounts of government deficit spending on infrastructure. Japan’s national debt is the highest in the world at over 200 percent of its GDP—about twice the proportion of U.S. debt and even higher than Greece’s debt relative to its GDP. “Except for government spending, exports have been the only area of strength in the Japanese economy for years. And there has been a close link between exports and GDP growth since 1990. That’s why the government in early 2010 began a campaign to spur exports of infrastructure goods such as bullet trains and nuclear reactors.” As with Germany, the options—in the case of Japan, prolonged government deficit spending for infrastructure and increased exports—used to sustain even modest growth in a situation of stable or declining population are open to only a few countries.

Rapid population aging—due to low or no population growth—confronts many of the wealthy countries and some not-so-wealthy ones. As Richard Jackson, the director of the Global Aging Initiative at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, explains: “Japan may be on the leading edge of a new economic era, an era of secular economic stagnation, which certain other fast-aging developed countries will soon enter.” Indeed, such stagnation is already an endemic problem (though not simply, or even mainly, for reasons of aging populations) in the triad of the United States/Canada, Western Europe, and Japan.

Combating Pollution and Resource Depletion/Misuse

The comprehensive 2012 report, People and the Planet by the Royal Society of London, included as one of its main conclusions that there is a need “to develop socio-economic systems and institutions that are not dependent on continued material consumption growth” (bold in original). In other words, a non-capitalist society is needed. Capitalism is the underlying cause of the extraordinarily high rate of resource use, mismanagement of both renewable and nonrenewable resources, and pollution of the earth. Any proposed “solution”—from birth control in poor countries to technological fixes to buying green to so-called “green capitalism” and so on—that ignores this reality cannot make significant headway in dealing with these critical problems facing the earth and its people.

Within the current system, there are steps that can and should be taken to lessen the environmental problems associated with the limits of growth: the depletion of resource taps and the overflowing of waste sinks, both of which threaten the future of humanity. Our argument, however, has shown that attempts to trace these problems, and particularly the problem of depletion natural resources, to population growth are generally misdirected. The economic causes of depletion are the issues that must be vigorously addressed (though population growth remains a secondary factor). The starting point for any meaningful attempt actually to solve these problems must begin with the mode of production and its unending quest for ever-higher amounts of capital accumulation regardless of social and environmental costs—with the negative results that a portion of society becomes fabulously rich while others remain poor and the environment is degraded at a planetary level.

It is clear then that capitalism, that is, the system of the accumulation of capital, must go—sooner rather than later. But just radically transcending a system that harms the environment and many of the world’s people is not enough. In its place people must create a socio-economic system that has as its very purpose the meeting of everyone’s basic material and nonmaterial needs, which, of course, includes healthy local, regional, and global ecosystems. This will require modest living standards, with economic and political decisions resolved democratically according to principles consistent with substantive equality among people and a healthy biosphere for all the earth’s inhabitants.

Notes

- ↩ Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, and Jørgen Randers, Beyond the Limits (London: Earthscan, 1992), 44–47.

- ↩ Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and William W. Behrens III, The Limits to Growth (New York: Universe Books, 1972).

- ↩ Malthus was not himself an environmental theorist, concerned with the environment, but an economic theorist developing an argument for subsistence wages. Nor did he point to scarcity of raw materials, arguing that raw materials “are in great plenty” and “a demand…will not fail to create them in as great a quantity as they are wanted.” Thomas Malthus, An Essay on the Principle of Population and a Summary View of the Principle of Population (London: Penguin, 1970), 205. See also John Bellamy Foster, Marx’s Ecology (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2000), 92–95.

- ↩ Donella Meadows, Jørgen Randers, and Dennis Meadows, The Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing, 2004), 54.

- ↩ Fred Magdoff, “The Political Economy of Biofuels,” Monthly Review 60, no. 3 (July–August 2008): 34–50.

- ↩ David A. Vaccari, “Phosphorus Famine: A Looming Crisis,” Scientific American (June 2009): 54–59.

- ↩ Tatyana Shumsky and John W. Miller, “Freeport CEO on Mining an Essential Metal,” Wall Street Journal, June 19, 2012, http://online.wsj.com.

- ↩ Fred Magdoff, “The World Food Crisis: Sources and Solutions,” Monthly Review 60, no. 1 (May 2008): 1–15.

- ↩ Fred Magdoff and Brian Tokar, eds., Agriculture and Food in Crisis: Conflict, Resistance, and Renewal (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2010). See also two reports of the Oakland Institute onUnderstanding Land Investment Deals in Africa, 2011, http://oaklandinstitute.org.

- ↩ Claire Provost, “New International Land Deals Database Reveals Rush to Buy Up Africa,”Guardian, April 27, 2012, http://guardian.co.uk.

- ↩ Mark Tran, “Africa Land Deals Lead to Water Giveaway,” Guardian, June 12, 2012, http://guardian.co.uk.

- ↩ Walid A. Abderrahman, Groundwater Resources Management in Saudi Arabia, Special Presentation at Water Conservation Workshop, Khober, Saudi Arabia, 2006, http://sawea.org.

- ↩ Damian Carrington and Stefano Valentino, “Biofuels Boom in Africa as British Firms Lead Rush on Land for Plantations,” Guardian, May 31, 2011, http://guardian.co.uk.

- ↩ Fred Pearce, The Land Grabbers (Boston: Beacon Press, 2012), x.

- ↩ Simon Goodley and Julian Borger, “Mining Firms Face Scrutiny Over Congo Deals,”Guardian, May 8, 2012, http://guardian.co.uk.

- ↩ John Terborgh, “The World Is in Overshoot,” New York Review of Books 56, no. 19 (December 3, 2009): 45–57.

- ↩ See Fred Magdoff and John Bellamy Foster, What Every Environmentalist Needs to Know About Capitalism (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2011), 77–83.

- ↩ K. William Kapp, The Social Costs of Business Enterprise (New York: Asia Publishing House, 1963).

- ↩ Scott Borgerson, “An Ice Cold War,” New York Times, August 8, 2007, http://nytimes.com.

- ↩ Michael Klare, The Race for What’s Left (London: Macmillan, 2012), 8.

- ↩ David Harvey, “The Political Implications of Population-Resources Theory,” May 23, 2010, http://climateandcapitalism.com.

- ↩ David Satterthwaite, “The Implications of Population Growth and Urbanization for Climate Change,” Environment and Urbanization 21, no. 2 (2009): 545–67.

- ↩ Karl Marx, Grundrisse (London: Penguin, 1973), 604–8.

- ↩ Gerhard Schroeder, “The Economy Uber Alles,” Wall Street Journal, December 30, 2003, http://online.wsj.com.

- ↩ Henry Chu, “As EU Migrants Flood Germany, Some Nations Fear A Brain Drain,” Los Angeles Times, March 12, 2012, http://articles.latimes.com.

- ↩ Adam Tooze, “Germany’s Unsustainable Growth,” Foreign Affairs 91, no. 5 (September/October 2012): 23–30.

- ↩ A. Gary Shilling, “As Japan Stops Saving, a Crisis Looms,” Bloomberg, June 6, 2012, http://bloomberg.com.

- ↩ Yuka Hayashi, “Japan Raises Sales Tax to Tackle Debt,” Wall Street Journal, August 11, 2012, http://online.wsj.com.

- ↩ See John Bellamy Foster and Robert W. McChesney, The Endless Crisis (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2012).

- ↩ Sir John Sulston, Chair of the Working Group, People and the Planet, The Royal Society (Britain), http://royalsociety.org.

- ↩ See discussion in Fred Magdoff and John Bellamy Foster, What Every Environmentalist Needs to Know About Capitalism, 124–31.